February 2025

An independent audit report

Child Care Licensing Capacity

623 Fort Street

Victoria, B.C.

V8W 1G1

The Honourable Raj Chouhan

Speaker of the Legislative Assembly

Province of British Columbia

Parliament Buildings

Victoria, British Columbia

V8V 1X4

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour to transmit to the Speaker of the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia the report, Child Care Licensing Capacity, with two independent audits.

We conducted the audits under the authority of section 11(8) of the Auditor General Act. All work in the audits was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001 – Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook – Assurance.

Sheila Dodds, CPA, CA, CIA

Acting Auditor General of British Columbia

Victoria, B.C.

February 2025

Audits at a glance

Why we did these audits

- ChildCareBC is the provincial plan introduced in 2018 to increase child care access, affordability, and quality. The provincial and federal governments have since funded 39,000 new child care spaces. About 31,000 more spaces are expected by 2028.

- To keep up with the growth, the ChildCareBC plan included a commitment to add to the capacity of regional health authorities to license, monitor and investigate child care facilities.

- B.C. separates child care licensing (led by the Ministry of Health and health authorities) from child care planning and funding (led by the Ministry of Education and Child Care). This structure requires effective coordination to implement child care policies and commitments.

About this report

- The Ministry of Education and Child Care leads implementation of ChildCareBC. Vancouver Coastal Health is one of five regional health authorities responsible for licensing, inspecting, and investigating child care facilities.

- Our two audits focused on ChildCareBC’s commitment to “increase capacity in health authorities to license new spaces, conduct investigations, and monitor compliance.”

- Our first audit looked at whether the Ministry of Education and Child Care had worked with health partners to implement the commitment.

- Our second audit considered if Vancouver Coastal Health assessed whether it had capacity to license new spaces, investigate complaints and monitor child care facilities.

- The audits are reported in separate chapters, each with its own conclusion.

Chapter 1: An audit of the Ministry of Education and Child Care’s commitment to increase the capacity of child care licensing programs

Objective

To determine whether the Ministry of Education and Child Care had effectively worked with health partners to implement the ChildCareBC plan’s commitment to increase capacity in health authorities to license new spaces, conduct investigations and monitor compliance.

Audit period: April 1, 2022 – July 31, 2024

Conclusion

The Ministry of Education and Child Care had not worked effectively with health partners (Ministry of Health and/or regional health authorities) to implement the ChildCareBC commitment to increase capacity in health authorities to license new spaces, conduct investigations, and monitor compliance in child care facilities. The ministry had not:

- coordinated with health partners to document expectations for implementing the commitment;

- monitored implementation of the commitment; or

- publicly reported progress on it.

As a result, the ministry did not know if health authorities have increased their capacity to license, investigate and monitor child care facilities.

The ministry has accepted all five recommendations on coordinating with health partners to document expectations for increasing capacity in health authorities’ child care licensing programs, and to monitor and report on progress.

What we found

The ministry had not coordinated with health partners to document expectations for increasing capacity in health authorities

- The ministry hadn’t coordinated with the Ministry of Health or regional health authorities to establish expectations for implementing the commitment. It hadn’t documented:

- roles and responsibilities;

- timelines and targets; and

- how the commitment will be funded.

- The ministry’s first meeting with health partners to discuss the commitment was in May 2024 – two years after the ministry was created in April 2022.

The ministry had not monitored or publicly reported on health partners’ implementation of the commitment

The ministry had not:

- confirmed whether health authorities had plans to increase capacity;

- obtained consistent and timely reporting on health partners’ implementation of the commitment;

- identified or managed risks to achieving the commitment; or

- worked with health partners to publicly report on the commitment.

Chapter 2: An audit of Vancouver Coastal Health’s child care licensing capacity

Objective

To determine whether Vancouver Coastal Health (VCH) assessed if it had the capacity to license new spaces, investigate complaints, and monitor compliance for child care facilities.

Audit period: April 1, 2022 – July 31, 2024

Conclusion

VCH did not adequately assess if it had capacity to license new spaces, investigate complaints, and monitor compliance for child care facilities.

While VCH established and monitored a key performance indicator for inspections, which it could use to help establish resource needs, it did not have key performance indicators or timelines for licensing or investigation activities. It also had not adequately determined the short-term and long-term resources needed to meet key performance indicators or timelines for these three activities.

The health authority has accepted all five recommendations on developing performance indicators, and using that information to determine the number of staff needed to meet program demands.

What we found

VCH had incomplete key performance indicators and timelines for its child care licensing and investigation activities

- VCH set and monitored a key performance indicator for routine inspections of child care facilities.

- VCH didn’t have a key performance indicator or timelines for processing child care licence applications or conducting investigations.

- Without a complete set of key performance indicators or timelines to measure against, it’s difficult for VCH to know whether it has enough resources to meet its expectations.

VCH did not adequately assess its resource needs

- VCH didn’t effectively evaluate the staffing levels needed to meet key performance indicators and timelines for its main activities.

- VCH had some relevant information to support long-term resource planning, but was missing critical information such as ChildCareBC space projections.

- Budgeted staffing levels haven’t changed since 2019, while the number of child care facilities has increased 19 per cent.

Background

High-quality child care can benefit the healthy development of children and enhance their readiness for school. It can let parents stay in the workforce, receive education, or perform other responsibilities.

Under the provincial Community Care and Assisted Living Act, which sets minimum standards for health, safety, and quality in licensed child care facilities, anyone who provides child care to more than two children or one sibling group requires a licence to operate. Licensed child care facilities must meet and maintain legislated requirements for health and safety, staffing qualifications, record keeping, space and equipment, child-to-staff ratios, and programming. The facilities are regularly inspected by staff from regional health authorities.

In October 2024, MECC reported there were 5,719 licensed child care facilities and 156,741 funded licensed child care spaces in the province. According to a Statistics Canada 2022 survey, 85 per cent of B.C. child care businesses were licensed.

ChildCareBC

In 2018, the provincial government introduced its 10-year plan, Caring for Kids, Lifting up Families: The Path to Universal Child Care (“ChildCareBC”). The plan sets forth funding, education, and partnership commitments to improve child care affordability, accessibility, and quality. As of March 31, 2024, the province had invested $4.4 billion in the plan.

MECC has led ChildCareBC since 2022 when the provincial Child Care Division moved to MECC from the Ministry of Children and Family Development.

Delivery of ChildCareBC’s commitments requires the combined efforts of public and private entities – from service providers and colleges to ministries and health authorities. This is particularly true for the plan’s commitments to “increase capacity in health authorities to license new spaces, conduct investigations, and monitor compliance,” which requires coordination between MECC, the Ministry of Health and the regional health authorities.

Federal-provincial child care agreements

The Ministry of Education and Child Care oversees B.C.’s commitments under federal-provincial child care agreements signed in 2018 and 2021 that include $3.5 billion in federal funding over five years (2021 to 2026) for regulated early learning and child care for children under age six.

The agreements cover many of the same commitments made in the ChildCareBC plan, with annual reporting requirements and other accountability measures. The ChildCareBC commitment to increase health authority capacity for licensing, monitoring and investigations isn’t in the federal-provincial agreements.

Responsibilities and relationships

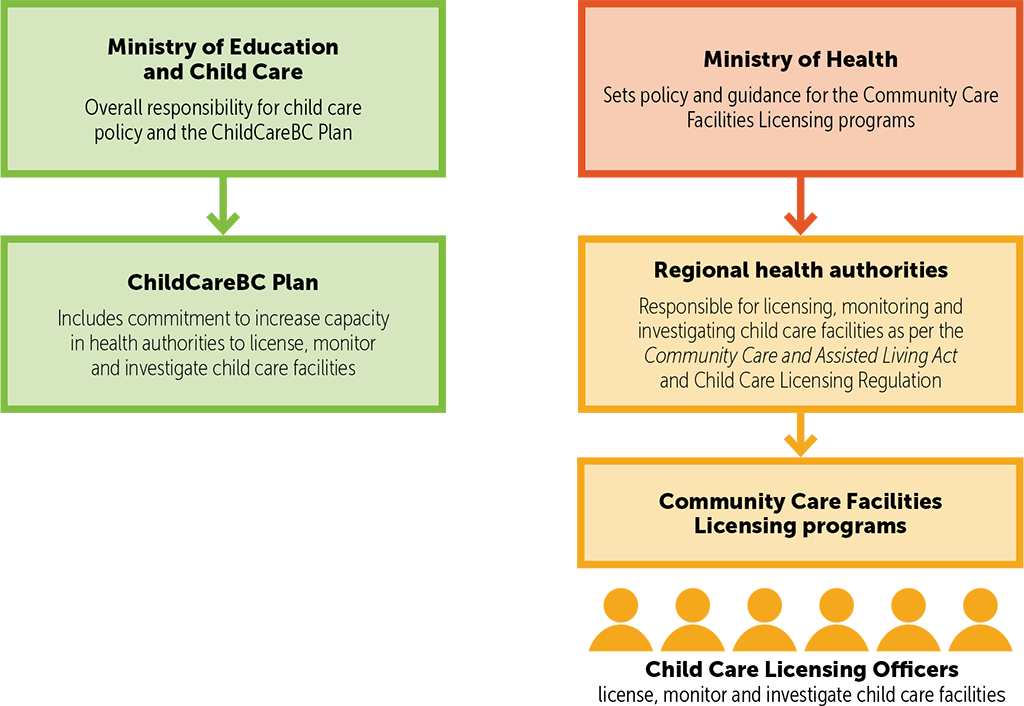

B.C. is the only Canadian jurisdiction where child care licensing (Ministry of Health and health authorities) is separate from child care planning and funding (MECC). The decentralized model requires effective coordination among the ministries and the five regional health authorities.

The five regional health authorities are responsible for licensing child care facilities and monitoring facilities’ compliance with the Community Care and Assisted Living Act and Child Care Licensing Regulation. Child care licensing officers issue new licences, conduct on-site routine inspections of child care facilities, and investigate complaints about facilities. Each health authority is responsible for developing policies, setting priorities, preparing and submitting budgets to the health minister, and allocating resources for health services within its region.

The Ministry of Health leads the provincial Community Care Facilities Licensing (CCFL) program. The program provides direction and support to the regional health authorities through the development and implementation of related regulations, standards, and policies (see the flow chart below).

Health authority licensing capacity is important for maintaining quality of care and safety of children, especially as the licensed child care system grows.

Since 2018, the province and the federal government have funded 39,000 new licensed child care spaces (MECC reports 20,000 now in operation and 19,000 underway). The goal is to create a total of about 70,000 spaces by 2028. The ChildCareBC plan also includes funding to encourage unlicensed care providers to become licensed.

Adequate resources are needed for regular inspections and to respond to complaints about child care facilities. The timely review and processing of child care licence applications also depends on sufficient staffing to avoid backlogs.

Licensing also affects affordability because only licensed facilities are eligible for certain provincial subsidies (i.e., $10 a Day, and the Child Care Fee Reduction Initiative).

Overview of entity responsibilities and relationships

Overview of entity responsibilities and relationships – text version

The Ministry of Education and Child Care holds responsibility for child care policy and the ChildCareBC plan. The ChildCareBC plan includes commitment to increase capacity in health authorities to license, monitor and investigate child care facilities.

The Ministry of Health holds responsibility for policy direction and guidance for the Community Care Facilities Licensing programs. These programs are administered by regional health authorities, which are responsible for licensing, monitoring, and investigating child care facilities in accordance with the Community Care and Assisted Living Act and the Child Care Licensing Regulation.

Within these programs, the Community Care Facilities Licensing Officers play a key role. They are responsible for licensing, monitoring, and investigating child care facilities to ensure they meet all required standards and regulations.

We conducted two audits, reported in separate chapters, each with its own conclusions:

Chapter 2: An audit of Vancouver Coastal Health’s child care licensing capacity

An independent audit report

Chapter 1: An audit of the Ministry of Education and Child Care’s commitment to increase the capacity of child care licensing programs

Background

The Ministry of Education and Child Care (MECC) is responsible for creating and funding child care spaces, regulating the child care work force, providing direction to school districts on child care policy, and establishing the Early Learning Framework. MECC is also responsible for the planning, development, and implementation of the ChildCareBC plan.

The ChildCareBC plan is the decade-long government initiative introduced in 2018 to add child care spaces and increase the affordability and quality of care. Until 2022, the Ministry of Children and Family Development was responsible for implementation of the ChildCareBC plan.

As of March 31, 2024, B.C. had invested $4.4 billion in ChildCareBC. Through the federal-provincial child care agreements, the federal government has provided B.C. with $3.5 billion for regulated early learning and child care for children under age six.

Parts of the ChildCareBC plan are beyond MECC’s jurisdiction and require coordination and consultation with other ministries and partners. This includes the commitment to increase capacity in health authorities to license, monitor and investigate child care facilities, which requires MECC to coordinate and consult with the Ministry of Health and the five regional health authorities.

Objective

The objective of the audit was to determine whether the Ministry of Education and Child Care had effectively worked with health partners to implement the ChildCareBC plan’s commitment to increase capacity in health authorities to license new spaces, conduct investigations and monitor compliance.

Scope

We audited the Ministry of Education and Child Care to see if they had effectively worked with health partners to implement the ChildCareBC plan’s commitment to increase capacity in health authorities, including:

- coordinating with health partners to document expectations for implementing the commitment;

- monitoring health partner implementation of the commitment; and

- working with health partners to publicly report progress on implementation of the commitment.

“Health partners” refers to either or both the Ministry of Health and the five regional health authorities.

We did not look at other commitments in the ChildCareBC plan.

We also did not look at the Ministry of Education and Child Care’s broader responsibilities for child care or how it is implementing the Declaration Act Action Plan commitment to “work in collaboration with B.C. First Nations, Métis, and Inuit People to implement a distinctions-based approach to support and move forward jurisdiction over child care for First Nations, Métis and Inuit Peoples who want and need it in B.C.”

The audit period was from April 1, 2022, to July 31, 2024. The start of the audit period coincided with the Ministry of Education and Child Care assuming responsibility for child care from the Ministry of Children and Family Development.

Conclusion

The Ministry of Education and Child Care had not worked effectively with health partners (Ministry of Health and/or regional health authorities) to implement the ChildCareBC commitment to increase capacity in health authorities to license new spaces, conduct investigations, and monitor compliance in child care facilities. The ministry had not:

- coordinated with health partners to document expectations for implementing the commitment;

- monitored implementation of the commitment; or

- publicly reported progress on it.

As a result, the ministry did not know if health authorities have increased their capacity to license, investigate and monitor child care facilities.

Findings and recommendations

Establishing expectations

The Ministry of Education and Child Care (MECC), as the lead ministry for ChildCareBC, is responsible for establishing expectations for meeting the plan’s commitment to increase capacity in health authorities to license new spaces, conduct investigations, and monitor compliance. This includes working with health partners to set objectives, establish performance measures, and manage risks.

The ministry had not coordinated with health partners to document expectations for increasing capacity in health authorities

What we looked for

We looked to see if MECC coordinated with health partners to establish and document clear roles, responsibilities, targets, timelines, and funding expectations for implementing the commitment to increase capacity in the health authorities to license, investigate and monitor child care facilities.

Learn more about the audit criteria.

What we found

We found that MECC had not coordinated with health partners to establish and document clear roles and responsibilities, targets and timelines, and funding expectations to implement the commitment to increase capacity in the health authorities to license, investigate and monitor child care facilities.

Roles and responsibilities not documented

We found that MECC had not coordinated with health partners to document roles and responsibilities for implementing the commitment.

We spoke with staff at the Ministry of Health and all five regional health authorities and found inconsistent understanding of the actions each party was responsible for taking related to the commitment. We heard that governance structures shifted after child care moved from the Ministry of Children and Family Development to MECC in April 2022. Since then, there had been a lack of coordinated cross-ministry collaboration.

MECC and Ministry of Health staff met in May 2024 to discuss establishing connection via a joint committee and a more formal governance structure between the two ministries. Neither the committee or governance structure were in place by the end of the audit period (July 31, 2024).

Timelines and targets not established

We found that MECC had not coordinated with health partners to establish targets and timelines for implementing the commitment to increase health authority capacity.

The health authorities indicated that they had each developed resource projections to support planned growth in child care spaces for years one to five (2018–22) and five to seven (2022–24) of the ChildCareBC plan.

Those projections were developed for funding requests coordinated and prepared by the Ministry of Children and Family Development prior to the audit period (and before responsibility for child care moved to MECC).

We found no evidence that the projections for additional staff were being used as targets by MECC, the Ministry of Health, or the health authorities. We also found no evidence of additional targets for the remaining years of the plan.

Funding process not coordinated

We found that MECC had not worked with health partners to document funding requests to increase capacity for child care licensing, monitoring, and investigations.

The province did not include amounts and funding sources in the development of the ChildCareBC plan. MECC’s annual base budget for ChildCareBC does not include funding for the commitment to increase health authority capacity. Instead, the province provided targeted funding for the commitment to the Ministry of Health’s budget through year seven of the ChildCareBC plan. There has been no funding allocated to the Ministry of Health for years 8-10.

We found that MECC and its health partners didn’t have a shared understanding of their roles and responsibilities for identifying funding needs. MECC hadn’t been collecting information about health authority capacity from the Ministry of Health. MECC hadn’t coordinated with health partners to identify whether additional funding was needed to ensure health authorities had capacity to license, investigate, and monitor child care facilities. Health authorities said that they had not been told about the process for requesting or receiving funding to increase capacity for the last three years of the plan.

Why this matters

There could be capacity pressures at the health authority level that impact MECC’s goal to increase access to high-quality, licensed child care spaces. In the absence of coordination with its health partners to establish and document expectations, MECC may be limited in its ability to effectively coordinate implementation of the commitment to increase the capacity of health authorities to license, monitor, and investigate child care facilities.

Recommendation

- We recommend that the Ministry of Education and Child Care work with health partners (the Ministry of Health and/or health authorities) to document expectations for implementing the commitment to increase the capacity of health authorities to license, monitor, and investigate child care facilities. This includes identifying roles and responsibilities, objectives, timelines and targets, and how the commitment will be funded.

Monitoring and reporting

Monitoring and reporting would enable MECC to understand how work is progressing, take corrective action where necessary, and maintain accountability on the commitment to increase health authority capacity to license, investigate and monitor child care facilities.

Monitoring and reporting, two key components of an effective accountability framework, are emphasized in the ChildCareBC plan:

“Creating universal child care is a major investment by government. It’s important for outcomes to be monitored and reported, and for the quality of care being delivered to be consistently monitored so parents can breathe easy, knowing their kids are being well-cared for.”

The ministry had not monitored or publicly reported on health partners’ implementation of the commitment

What we looked for

We looked for evidence that MECC had coordinated with health partners to confirm their plans to increase capacity, obtain reports on timelines and targets, identify and manage risks, and publicly report its progress on the implementation of the commitment.

Learn more about the audit criteria.

What we found

We found that MECC hadn’t coordinated with health partners to confirm and monitor plans to increase capacity in health authorities and had not publicly reported on its progress. It hadn’t obtained consistent and timely reporting from its health partners or monitored risks to the implementation of the commitment.

No monitoring of health authority capacity

MECC doesn’t direct how health authorities build capacity, but it is responsible for coordinating with health partners to ensure the commitment is implemented. We found that MECC had not confirmed or monitored whether health authorities had plans to increase their capacity to license, monitor, and investigate child care facilities.

Health authorities need information about anticipated growth in spaces in order to develop capacity plans that accommodate future demand. MECC sets targets for new spaces through its new spaces fund, start-up grants, and other child care funding but it had not shared that information with the Ministry of Health or the regional health authorities.

The health authorities reported that they had not been asked for resourcing plans or funding requests for the remainder of the ChildCareBC plan, and they haven’t received MECC’s projections for new child care facilities and spaces. This limits the ability of health authorities to make plans for increasing capacity that align with anticipated growth.

No consistent and timely reporting

We examined whether MECC worked with health partners to get consistent and timely reporting on timelines and targets related to the commitment. We found that MECC didn’t have the information because it had not established timelines and targets.

MECC did request some basic program information from the Ministry of Health in February 2024, including:

- the number of licensing officers available for child care facilities (annually) since 2018;

- the average time for new child care facilities to become licensed by health authorities; and

- any data or metrics on projected demand or need for more licensing officers.

MECC learned through the request that the Ministry of Health doesn’t collect much of this data. As a result, it only received the number of child care licensing officers working in health authorities between 2022 and 2024.

MECC indicated that its reporting relationships are between ministries, not with health authorities. We found that MECC was aware of information sharing challenges with the different data systems used by the health authorities. It had taken steps to develop a formal agreement for sharing child care information with health partners.

However, MECC hadn’t coordinated with health partners to find a solution or set expectations for sharing progress updates, including the type of information each party would like to receive from the others, how, and when.

Risks not identified or managed

Risk management in public sector organizations includes identifying and assessing key strategic, operational and financial risks, deciding on appropriate responses, and providing assurance that the responses are effective. We looked at whether MECC worked with health partners to identify, mitigate, and monitor risks to achieving the commitment to increase health authority capacity. We found they did not.

MECC assumed that the Ministry of Health would advise them of risks to implementing the commitment to increase child care licensing officer capacity in the health authorities, and as a result did not proactively seek out that information.

The health authorities all indicated that understaffing and increasing demand for child care licensing, investigation, and monitoring services was affecting their ability to maintain manageable caseloads for child care licensing officers.

They told us that the increased volume and complexity of licence applications, plus routine inspections, took time from educating and building relationships with child care providers, which is needed for incident prevention and long-term quality assurance.

The health authorities also told us they don’t discuss existing capacity, the ChildCareBC commitment, or their concerns related to the commitment with either MECC or the Ministry of Health. As a result, MECC was not aware of the health authorities’ capacity concerns.

No public reporting on progress

We found that MECC had not publicly reported its progress on the ChildCareBC commitment to increase capacity in health authorities to license new spaces, conduct investigations, and monitor compliance.

We found that MECC released two public reports on the overall progress of the ChildCareBC plan, but neither report included updates on the commitment to increase health authority capacity to license, investigate and monitor child care facilities.

As noted, we found that MECC had not collected information to monitor implementation of the commitment, which is necessary for public progress reporting.

Why this matters

The commitment to increase capacity in health authorities was made to ensure health authorities can accommodate the growth of affordable, accessible child care spaces while maintaining the quality of licensed care.

Without established communication channels with the Ministry of Health to share information, monitor capacity, and manage risks, MECC was unable to confirm whether the commitment has been effectively implemented.

The absence of regular public reports on the ChildCareBC commitment to increase health authority capacity erodes transparency and accountability for government’s actions on this commitment.

Recommendations

We recommend that the Ministry of Education and Child Care work with health partners (the Ministry of Health and/or health authorities) to:

- Ensure health authorities develop plans to increase capacity to license, investigate and monitor child care facilities that are aligned with existing and anticipated growth in child care spaces.

- Monitor progress against timelines and targets for how the commitment to increase capacity in health authorities to license, investigate, and monitor child care facilities will be achieved.

- Identify, monitor, and mitigate risks to implementing the commitment to increase capacity in health authorities to license, investigate, and monitor child care facilities.

- Annually and publicly report on the progress of the commitment to increase capacity in health authorities to license, investigate, and monitor child care facilities.

An independent audit report

Chapter 2: An audit of Vancouver Coastal Health’s child care licensing capacity

Background

Vancouver Coastal Health (VCH) is one of five B.C. regional health authorities. It serves 1.25 million people (or about 25 per cent of the province’s population), including about 55,000 children age five and under. BC Stats projects the region’s population of kids in that age group will rise by roughly 15 per cent in the next decade.

VCH’s range of health care programs and services includes the Community Care Facilities Licensing (CCFL) program. This program is responsible for licensing child care facilities and residential care facilities and monitoring facilities’ compliance with the Community Care and Assisted Living Act. Within its CCFL program, VCH has separate teams of child care licensing officers and residential care licensing officers. Child care licensing officers have specialized knowledge about child care and are required to have an Early Childhood Educator designation.

The Community Care and Assisted Living Act and the Child Care Licensing Regulation set minimum standards for health, safety, and quality in licensed child care facilities, including staff qualifications, record keeping, space and equipment, child-to-staff ratios, and programming.

VCH child care licensing officers:

- Issue new licences and amendments. Licensing officers provide guidance to applicants, assess application materials, conduct inspections of the proposed facility to determine compliance with legislative and regulatory requirements, and approve or deny applications;

- Conduct routine on-site inspections of all child care facilities. Licensing officers assess compliance with the Community Care and Assisted Living Act and the Child Care Licensing Regulation by inspecting the physical space, reviewing permits and files, and observing program operations to identify and prevent risks to the health and safety of children; and

- Investigate complaints. Licensing officers collect and review evidence to determine if operators are not complying with the act or regulation. They take action to suspend a licence if necessary.

The number of licensed child care facilities in VCH has increased since the ChildCareBC plan was introduced in 2018, rising from 1,753 to 2,079 (+19 per cent) between 2019 and 2023.

ChildCareBC commits to increasing capacity in health authorities to license new spaces, conduct investigations and monitor compliance.

Objective

The objective of the audit was to determine whether Vancouver Coastal Health assessed if it had the capacity to license new spaces, investigate complaints, and monitor compliance for child care facilities.

Scope

We audited Vancouver Coastal Health to see if it had assessed whether it had the capacity to license new spaces, investigate complaints, and monitor compliance for child care facilities, including whether Vancouver Coastal Health:

- established relevant key performance indicators or timelines for its child care licensing, investigation and monitoring activities;

- regularly reviewed whether it met its key performance indicators and timelines; and

- identified the resources needed to meet its key performance indicators and timelines in the short- and long-term.

The audit was focused on Vancouver Coastal Health’s capacity planning process. The audit did not look at the quality of child care, or the outcome of inspections and investigations.

Vancouver Coastal Health was selected because it services a large population, has a significant number of child care facilities, and includes urban and rural communities.

The audit period was from April 1, 2022, to July 31, 2024.

Conclusion

The Ministry of Education and Child Care had not worked effectively with health partners (Ministry of Health and/or regional VCH did not adequately assess if it had capacity to license new spaces, investigate complaints, and monitor compliance for child care facilities.

While VCH established and monitored a key performance indicator for inspections, which it could use to help establish resource needs, it did not have key performance indicators or timelines for licensing or investigation activities. It also had not adequately determined the short-term and long-term resources needed to meet key performance indicators or timelines for these three activities.

Findings and recommendations

Establishing and monitoring key performance indicators and timelines

Organizations use key performance indicators, or KPIs, to set expectations and evaluate how well they are achieving goals. KPIs also provide valuable information for capacity planning as they provide a benchmark for organizations to establish staffing needs. For example, if an organization’s KPI is that it wants to complete 10 activities a year, it can then identify the staffing needed to reach that goal.

Organizations can also establish timelines to set expectations of how long certain processes should take staff to complete. By monitoring against timelines, an organization can assess whether staff are able to complete tasks in a timely manner.

Monitoring KPIs and timelines can also alert organizations where staffing may be falling short if an organization is struggling to meet its goals.

The Provincial Guide to Community Care Facility Licensing, developed by the Ministry of Health and the regional health authorities, describes how child care licensing program activities should be carried out.

However, the Ministry of Health, in the guide or elsewhere, doesn’t establish KPIs or timelines for the health authorities. The governing legislation also doesn’t prescribe minimum timelines or frequency requirements for licensing, monitoring, or investigations of child care facilities.

Each health authority can establish its own KPIs and timelines for its child care licensing, inspection, and investigation activities.

VCH had incomplete key performance indicators and timelines for its child care licensing and investigation activities

What we looked for

We first looked at whether VCH established relevant KPIs or timelines for inspection, licensing, and investigation activities that could be used to inform capacity planning. We also examined whether VCH had access to, and regularly reviewed, accurate and reliable reports to monitor KPIs and timelines.

Learn more about the audit criteria.

What we found

We found that VCH established and monitored a relevant KPI and timeline for inspections, but not for new licence applications or investigations.

VCH set and monitored a KPI for routine inspections

We found that VCH established a relevant KPI for routine inspection frequency tailored to the risk level of each facility (see table) in its region. Licensing officers were instructed to use a risk assessment tool developed by the Ministry of Health and the regional health authorities to determine the risk rating and inspection frequency for child care facilities.

VCH inspection KPI for child care facilities

| Child care facility risk level | Inspection frequency |

|---|---|

| Low risk | Once per year |

| Moderate risk | Twice per year |

| High risk | Three times per year |

We found that VCH regularly reviewed whether staff met the KPI for inspections. It did so by monitoring a performance dashboard that compared the total number of routine inspections completed in a fiscal year to the expected number.

VCH set a target for completing approximately 25 per cent of annual inspections each quarter of the fiscal year and 100 per cent by year-end. In each of the past two fiscal years, VCH completed over 90 per cent of its expected routine inspections:

| Fiscal year | Expected routine inspections | Completed routine inspections | Completion rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2022/23 | 1,673 | 1,560 | 93.25% |

| 2023/24 | 1,705 | 1,630 | 95.6% |

VCH did not set a KPI or timeline for processing child care licence applications

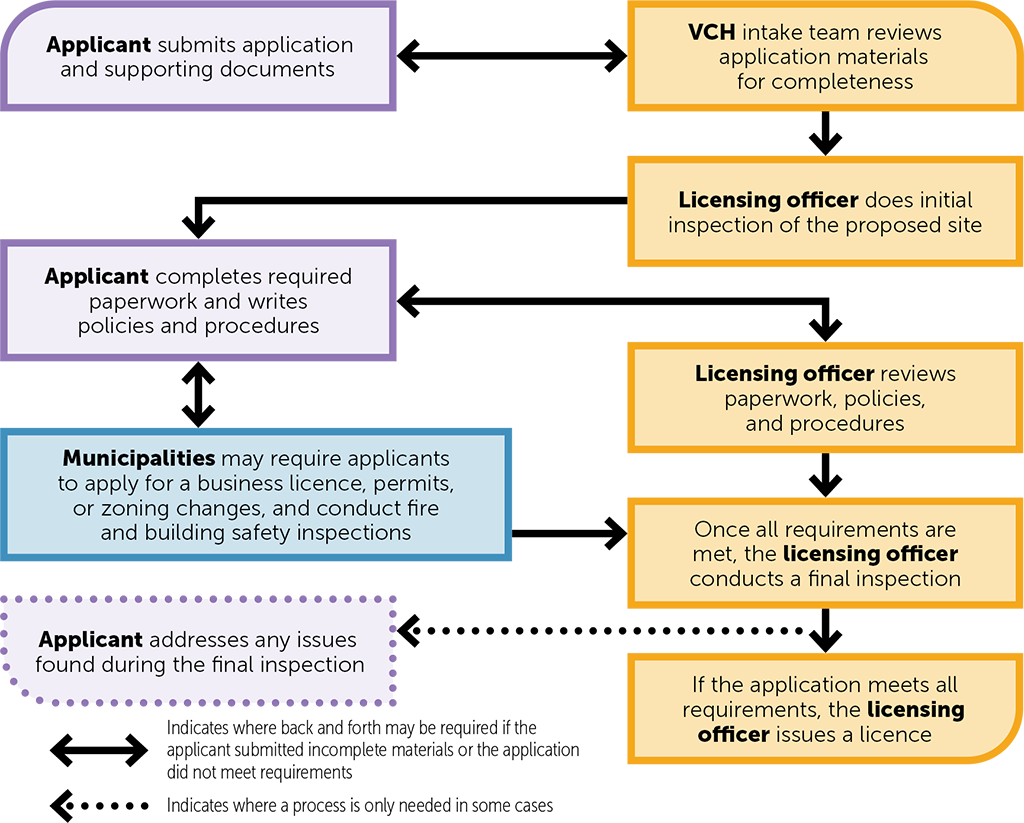

We found that VCH didn’t establish a KPI or timeline for its child care licence application process. VCH also didn’t monitor how long the licence application process took (see the flow chart on the following page) or how much staff time was needed to process licence applications.

VCH’s child care licence application process

VCH’s child care licence application process – text version

The process begins when the applicant submits their application along with the required supporting documents. The Vancouver Coastal Health intake team reviews the materials to ensure they are complete. If any documents are missing or clarification is needed, there may be back-and-forth communication between the applicant and the intake team. Once the application is complete, a licensing officer reviews the application. At this step, the applicant may need to submit additional paperwork or refine their policies and procedures, leading to further communication to ensure all requirements are met.

In some cases, municipalities may require the applicant to apply for a business license, obtain permits, request zoning changes, or undergo fire and building inspections. Once these steps are completed, the licensing officer conducts a final inspection. If any issues are found, the applicant must address them before the licensing officer can move the application forward.

When all requirements are met, the licensing officer issues the licence, allowing the applicant to begin operations.

Source: Prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of B.C. based on VCH’s Licensing Application Guide – Group Child Care and the provincial Guide to Community Care Facility Licensing.

VCH had approximate timelines for the initial stages of the application process (intake team’s review of application and initial inspection) that it communicated to applicants to set expectations, but we found that the timelines were not used to monitor staff capacity.

VCH indicated there are challenges with developing standard targets that could be used to develop a KPI for processing child care licence applications because other parties (the applicant, municipality, or fire department) are responsible for some steps in the application process and may cause delays.

We heard in interviews with program staff that licence applications were taking increasing amounts of staff time. Licensing officers indicated there was an increase in applicants without experience running a child care facility, requiring more support from VCH during the application process.

We found that while VCH started tracking the number of incoming licence applications in June 2023, it did not track how long the process took or how many staff hours were used to process applications. This information could help VCH determine the staff needed to meet demand.

VCH set a timeline for the intake of investigations, but not other steps

There are seven steps in VCH’s investigation process. We found that VCH had established response timelines for the first phase (intake) but didn’t track whether staff were meeting the timelines. VCH also didn’t have a KPI, timeline, or data to monitor the other investigation phases or the overall process.

VCH’s investigation process includes the following seven steps:

- Intake

- Planning

- Notification, inspections and health and safety plans

- Collection of evidence

- Analysis of evidence

- Communication

- Summary of investigation

During the intake phase, licensing officers are to review complaints upon receipt (within one working day) then initiate the investigation (site visit or contact with the facility) within one to three working days depending on their initial assessment of risk posed to the health and safety of children in the facility.

Licensing officers classify incoming complaints based on risk:

- Level 1 – low risk to health and safety, primarily operational in nature (e.g., diapering not happening often enough, service delivery problem).

- Level 2 – moderate risk to health and safety, but doesn’t pose an immediate risk (e.g., practice issues, not meeting staff-to-child ratios, preventable injury, staff qualifications).

- Level 3 – high risk to health and safety, need for immediate intervention (e.g., abuse or neglect allegations, physical restraint, child missing). May involve referral to police or Ministry of Children and Family Development if there are allegations of abuse or neglect.

Initial response timelines serve the important purpose of requiring licensing officers to respond promptly to complaints to ensure the health and safety of children. But that timeline alone doesn’t provide insight into whether program staff have capacity to complete investigations in a timely manner.

While VCH had a process for supervisors to review investigation files to ensure licensing officers met quality expectations, VCH didn’t have data to monitor whether staff were meeting the initial response timelines across the program.

VCH pointed to challenges with developing a standard timeline for investigations. The work involved can vary with the nature of the complaint. We heard from program staff that investigations may be concluded in a few days or take as long as two months depending on the severity and scope of the alleged contravention and investigation.

However, like what we found with licence applications, VCH didn’t monitor data to track trends in investigations, such as how long investigations took year over year, or how much staff time was spent completing investigations.

Because of their varying nature, it may not be appropriate to establish a KPI for investigations. However, VCH could review data about investigations to establish a baseline of approximately how long the different steps in the investigation process take. Monitoring against this expectation would enable VCH to assess whether staff are able to complete investigations in a timely manner, which could feed into VCH’s capacity planning process.

Why this matters

Without setting a KPI or timeline, or monitoring how long staff take to complete licensing and investigations, VCH did not know whether staff were able to process applications and complete investigations in a timely manner. This information is key to determining the appropriate number of staff required to meet growing demand.

If staffing remains the same while applications and child care facility numbers continue to increase, licence applications could take longer to process and families may have to wait longer for new spaces to become available. It may also take VCH longer to resolve complaints.

Recommendation

We recommend that Vancouver Coastal Health:

- Collect data on its child care licensing process (e.g., staff time, number of applications), and use the data to determine what an appropriate key performance indicator or timeline would be.

- Collect data on its child care investigation process (e.g., staff time, number of investigations, risk assessments) and use the data to determine what an appropriate key performance indicator or timeline would be.

- Monitor whether staff are meeting the key performance indicator or timeline it develops for child care licensing and investigations.

Identifying resource needs

Resource planning can help an organization achieve its objectives and minimize risks to service delivery by ensuring it has the right resources in place. Once an organization has determined staffing needs, good practice recommends comparing them with available staffing to determine if there’s a gap.

VCH did not adequately assess its resource needs

What we looked for

We examined whether VCH identified the resources it needed for its child care licensing, monitoring, and investigation activities in the short-term (current fiscal year) and long-term (multi-year) based on the KPIs or timelines it established. We also examined whether VCH had used up-to-date information to identify its resource needs, such as anticipated population growth and the projected number of new child care spaces.

Learn more about the audit criteria.

What we found

We found that VCH did not identify the resources it needed for its child care licensing, monitoring, and investigation activities in the short- or long-term based on relevant performance metrics and up-to-date information. VCH had collected some information about resourcing gaps and projected growth in its child care licensing program, but without KPIs or timelines for its licensing and investigation activities, VCH was limited in its ability to determine how many staff were needed to meet its expectations.

In July 2023, VCH completed a qualitative analysis of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT analysis) for the child care licensing program that identified issues with vacancies, staff shortages, recruitment and retention, and staff burnout. The analysis noted that current resources were insufficient and more full-time staff were needed.

VCH also hired a consultant in 2023 to project future demands of the broader Health Protection department (which includes the Community Care Facilities Licensing program) to plan for future office space. The report projected increased demands on the child care licensing program based on population trends and historical workload data.

While the SWOT analysis and the consultant’s report both suggested VCH had insufficient resources to meet current and future demand, we found that they lacked key data to adequately confirm the resources VCH needs to meet expectations. Firstly, they were not based on staff’s ability to meet expectations for licensing and investigations because (as we noted above) VCH had not established KPIs or timelines for these activities. They also lacked up-to-date data from the Ministry of Health or the Ministry of Education and Child Care (MECC) about how ChildCareBC initiatives are expected to increase the number of child care facilities in VCH. VCH said it didn’t routinely receive region-specific information about projections for new child care spaces, targets, or funding to assist with capacity planning.

We found that VCH’s baseline staffing of 21.8 child care licensing officers had stayed the same since 2019, when VCH received funding from the Ministry of Health for an additional three licensing officers to support the ChildCareBC plan. While staffing levels were unchanged since 2019, the number of child care facilities within VCH increased 19 per cent, from 1,753 to 2,079 between 2019 and 2023 (see bar chart).

Most staff we interviewed said that VCH didn’t have enough child care licensing officers to keep up with routine inspections, investigations, and new licence applications.

Number of licensed child care facilities in VCH

Number of licensed child care facilities in VCH – text version

2019: 1,753 facilities

2020: 1,858 facilities

2021: 1,914 facilities

2022: 2,035 facilities

2023: 2,079 facilities

Source: Prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of British Columbia, with data provided by the Vancouver Coastal Health Authority.

*Number of child care facilities includes active facilities, proposed facilities, temporarily closed facilities, and closed facilities that were active at some point during the year.

VCH informed us that its attention had been focused on filling vacancies in the existing team rather than undertaking resource planning. VCH also noted that staff vacancies impacted its ability to evaluate its resource needs, as VCH was unable to monitor how the child care licensing program would operate with a fully staffed team.

During our audit period (April 1, 2022 – July 31, 2024), VCH filled 12 vacant full-time licensing officer or senior licensing officer positions. As of June 2024, VCH had two vacancies for child care licensing officers and two child care licensing officers were on extended leave (six months or longer).

Why this matters

There is a risk that VCH has insufficient resources to effectively and efficiently conduct its child care licensing, inspection, and investigation activities, now and into the future.

The lack of a resource planning process also limits VCH’s ability to develop informed funding requests for additional resources.

Recommendations

We recommend that Vancouver Coastal Health:

- Identify the resources needed to meet current-year program demands based on key performance indicators or timelines for its child care licensing, inspection and investigation activities.

- Develop a multi-year plan that identifies the number and type of staff needed to meet projected program demands based on up-to-date information (such as anticipated population growth and the planned number of new child care spaces).

About the audits

We conducted these audits under the authority of section 11(8) of the Auditor General Act and in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001 – Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook – Assurance. These standards require that we comply with ethical requirements and conduct the audit to independently express a conclusion against the objective of the audit.

A direct audit involves understanding the subject matter to identify areas of significance and risk, and to identify relevant controls. This understanding is used as the basis for designing and performing audit procedures to obtain evidence on which to base the audit conclusion.

Chapter 1: An audit of the Ministry of Education and Child Care’s commitment to increase the capacity of child care licensing programs

The audit procedures we conducted for the audit of the Ministry of Education and Child Care included document reviews and interviews with the ministry, the Ministry of Health, and the five regional health authorities.

Audit report date: February 8, 2025

We believe the audit evidence we have obtained is sufficient and appropriate to provide a basis for our conclusions.

Chapter 2: An audit of Vancouver Coastal Health’s child care licensing capacity

The audit procedures we conducted for the audit of the Vancouver Coastal Health Authority included document reviews, data analysis and interviews with management and program staff.

Audit report date: February 8, 2025

We believe the audit evidence we have obtained is sufficient and appropriate to provide a basis for our conclusions.

Our office applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Management (CSQM 1), and we have complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the code of professional conduct issued by the Chartered Professional Accountants of British Columbia that are relevant to these audits.

Our office applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Management (CSQM 1), and we have complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the code of professional conduct issued by the Chartered Professional Accountants of British Columbia that are relevant to these audits.

Sheila Dodds, CPA, CA, CIA

Acting Auditor General of British Columbia

Victoria, B.C.

Appendix A: Recommendations and auditee responses

Chapter 1: An audit of the Ministry of Education and Child Care’s commitment to increase the capacity of child care licensing programs

Recommendation 1: We recommend that the Ministry of Education and Child Care work with health partners (the Ministry of Health and/or health authorities) to document expectations for implementing the commitment to increase the capacity of health authorities to license, monitor and investigate child care facilities. This includes identifying roles and responsibilities, objectives, timelines and targets, and how the commitment will be funded.

Recommendation 1 Response: The ministry agrees with the recommendation.

A cross-ministry committee chaired by the Assistant Deputy Minister of Child Care Division within MECC, and the Assistant Deputy Minister of Senior Services Division within the Ministry of Health (MOH) has been established. The committee will discuss shared responsibilities relating to child care, including collaborating and coordinating to support mutual goals and objectives and publicly reporting on commitments.

The Terms of Reference for the committee defines roles and responsibilities of each ministry as follows:

- MECC: information sharing to support future planning of growth areas, reporting, supporting funding requests and other requests from MOH as needed.

- MOH: monitoring of health authorities including coordinating to establish targets and timelines, monitoring health authority performance, communicating funding needs and seeking funding as and when needed.

This committee includes the following two subcommittees:

- Operational sub-committee will discuss shared operational objectives, facilitate relationship building and information sharing, support health authorities and ensure they are aware of policy changes.

- Strategic Policy sub-committee will provide a primary point of cross ministry connection to address and discuss shared and interconnected child care initiatives and issues.

Recommendation 2: We recommend that the Ministry of Education and Child Care work with health partners (the Ministry of Health and/or health authorities) to ensure health authorities develop plans to increase capacity to license, monitor and investigate child care facilities that are aligned with existing and anticipated growth in child care spaces.

Recommendation 2 Response: The ministry agrees with the recommendation.

MOH will ensure health authorities develop plans to ensure current and future licensing officer capacity are aligned with the current and anticipated number of child care spaces within their respective regions.

MECC will support this planning by providing advance information of regional anticipated growth in child care spaces to MOH, through the established ADM Committee.

Recommendation 3: We recommend that the Ministry of Education and Child Care work with health partners (the Ministry of Health and/or health authorities) to monitor progress against timelines and targets for how the commitment to increase capacity in health authorities to license, investigate and monitor child care facilities will be achieved.

Recommendation 3 Response: The ministry agrees with the recommendation.

MOH will gather information from health authorities to monitor progress against targets and timelines established under recommendations 1 and 2. Progress will be reported to the ADM committee.

Issues will be raised and discussed at the Operational Sub-committee and/or the Strategic Policy Sub-committee, as needed.

Recommendation 4: We recommend that the Ministry of Education and Child Care work with health partners (the Ministry of Health and/or health authorities) to identify, monitor and mitigate risks to implementing the commitment to increase capacity in health authorities to license, investigate and monitor child care facilities

Recommendation 4 Response: The ministry agrees with the recommendation.

MECC and MOH will develop a risk register to assess and monitor risks to implementing the commitment to ensure licensing officer capacity is commensurate with current and anticipated sector growth in child care.

The risk register will be updated by the Strategic Policy Sub-Committee and reported to the ADM committee.

Recommendation 5: We recommend that the Ministry of Education and Child Care work with health partners (the Ministry of Health and/or health authorities) to annually and publicly report on the progress of the commitment to increase capacity in health authorities to license, investigate and monitor child care facilities.

Recommendation 5 Response: The ministry agrees with the recommendation.

The Early Learning Child Care Act received Royal Assent and was brought into force September 1, 2024. Under the Act, MECC is required to publicly report annually on the progress of the ChildCareBC plan. This annual reporting will provide a platform to report on the progress of this commitment.

MECC will lead the development of the report and coordinate with the Strategic Policy Sub-Committee for annual updates on the progress of the commitment.

Chapter 2: An audit of Vancouver Coastal Health’s child care licensing capacity

Recommendation 1: We recommend that VCH collect data on its child care licensing process (e.g., staff time, number of applications), and use the data to determine what an appropriate key performance indicator or timeline would be.

Recommendation 1 Response: VCH agrees with the recommendation and will establish an Application KPI.

Application KPI – A key performance indicator will be developed that will track the time from the date a licence application is submitted to the date a licence is issued, with performance expectations for the steps within the control of VCH Licensing Officers.

Recommendation 2: We recommend that VCH collect data on its child care investigation process (e.g., staff time, number of investigations, risk assessments), and use the data to determine what an appropriate key performance indicator or timeline would be.

Recommendation 2 Response: VCH agrees with the recommendation and will establish an Investigation KPI.

Investigation KPI – A key performance indicator will be developed that will track the date from when an investigation is initiated to the date when the investigation is closed, with performance expectations for staff for key steps within the investigation.

Recommendation 3: We recommend that VCH monitor whether staff are meeting the key performance indicator or timeline it develops for child care licensing and investigations.

Recommendation 3 Response: VCH agrees with the recommendation.

Within 12 months of establishing the KPIs, VCH will determine suitable targets and begin monitoring staff performance against the targets.

Recommendation 4: We recommend that VCH identify the resources needed to meet current-year program demands based on key performance indicators or timelines for its child care licensing, inspection and investigation activities.

Recommendation 4 Response: VCH agrees with the recommendation.

Using the initial Application and Investigation KPIs and targets, VCH will use that data to assess its short-term resource needs to meet its licensing, inspection and investigation demands.

Recommendation 5: We recommend that VCH develop a multi-year plan that identifies the number and type of staff that would be needed to meet projected program demands based on up-to-date information (such as anticipated population growth and the planned number of new child care spaces).

Recommendation 5 Response: VCH agrees with the recommendation.

Within 12 months of establishing the Application and Investigation KPIs and targets, VCH will use the data collected and data on projected population growth and child care demand to develop a multi-year staffing plan to meet projected program demands.

Appendix B: Audit criteria

Chapter 1: An audit of the Ministry of Education and Child Care’s commitment to increase the capacity of child care licensing programs

Objective: To determine whether the Ministry of Education and Child Care (MECC) had effectively worked with health partners to implement the ChildCareBC plan’s commitment to increase capacity in health authorities to license new spaces, conduct investigations and monitor compliance.

Criterion 1.1: MECC had coordinated with the Ministry of Health (MOH) and/or Health Authorities (HAs) to document expectations for implementing the commitment.

1.1.1 MECC coordinated with MOH and/or HAs to establish roles and responsibilities to implement the commitment.

1.1.2 MECC coordinated with MOH and/or HAs to establish timelines and targets to implement the commitment.

1.1.3 MECC coordinated with MOH and/or HAs to confirm how the commitment will be funded.

Criterion 1.2: MECC had monitored MOH and/or HAs implementation of the commitment.

1.2.1 MECC confirmed that MOH and/or HAs developed plans to increase HA capacity that align with anticipated growth in new child care spaces.

1.2.2 MECC obtained consistent and timely reporting against timelines and targets from MOH and/or HAs.

1.2.3 MECC analyzed reporting to identify risks to timelines and targets provided by MOH and/or HAs.

1.2.4 MECC worked with MOH and/or HAs to mitigate risks.

Criterion 1.3: MECC worked with MOH and/or HAs to publicly report progress on implementation of the commitment.

Chapter 2: An audit of Vancouver Coastal Health’s child care licensing capacity

Objective: To determine whether Vancouver Coastal Health (VCH) assessed if it had the capacity to license new spaces, investigate complaints, and monitor compliance for child care facilities.

Criterion 1.1: VCH established relevant key performance indicators or timelines for its child care licensing, investigation and monitoring activities.

Criterion 1.2: VCH identified the resources it needs to meet key performance indicators or timelines for its child care licensing, investigation, and monitoring activities.

1.2.1 VCH identified the resources it needs to meet its licensing, investigation, and monitoring activities in the short-term (current fiscal year).

1.2.2 VCH identified the resources it needs to meet its licensing, investigation, and monitoring activities in the long-term (multi-year).

1.2.3 VCH used up-to-date information (such as anticipated population growth, number of new child care spaces) to identify the resources it needs.

1.2.4 VCH compared the resources it needs against the resources it has to identify resourcing gaps.

Criterion 1.3: VCH regularly reviewed whether it met key performance indicators or timelines for its child care licensing, investigation and monitoring activities.

1.3.1 VCH had accurate and reliable reports to monitor its key performance indicators or timelines.

1.3.2 VCH regularly reviewed reports that monitor its key performance indicator or timelines to assess progress and achievement.

1.3.3 VCH addressed barriers to meeting its key performance indicators or timelines.

Appendix C: Abbreviations

| MECC | Ministry of Education and Child Care |

| MOH | Ministry of Health |

| VCH | Vancouver Coastal Health Authority |

| CCFL | Community Care Facilities Licensing program |

| KPI | Key performance indicator |

Contents

Chapter 2: An audit of Vancouver Coastal Health’s child care licensing capacity

Appendix A: Recommendations and auditee responses

The Office of the Auditor General of British Columbia acknowledges with respect that we conduct our work on Coast Salish territories. Primarily, this is on the Lekwungen-speaking people’s (Esquimalt and Songhees) traditional lands, now known as Victoria, and the W̱SÁNEĆ people’s (Pauquachin, Tsartlip, Tsawout and Tseycum) traditional lands, now known as Saanich.

Information presented here is the intellectual property of the Auditor General of British Columbia and is copyright protected in right of the Crown. We invite readers to reproduce any material, asking only that they credit our office with authorship when any information, results or recommendations are used.